"The cost of AI will eventually converge with the cost of energy"

The energy gluttony of AI, organoid intelligence, 9 simple changes you can make to your prompts to use Large Language Models more sustainably & a great interview by Peter Diamandis with Eric Schmidt

In the rivers and lakes of South Asia lives a seemingly humble little fish, which is actually a marvel of biological engineering. It manages all the activity required for its survival while consuming only minimal energy.

The larva of the Danio rerio, also known by some as the "zebra fish" due to its stripes, navigates waters, hunts prey, and evades predators using just 0.1 microwatts of energy for all this vital activity. And it’s not the only biological organism with such enviable performance.

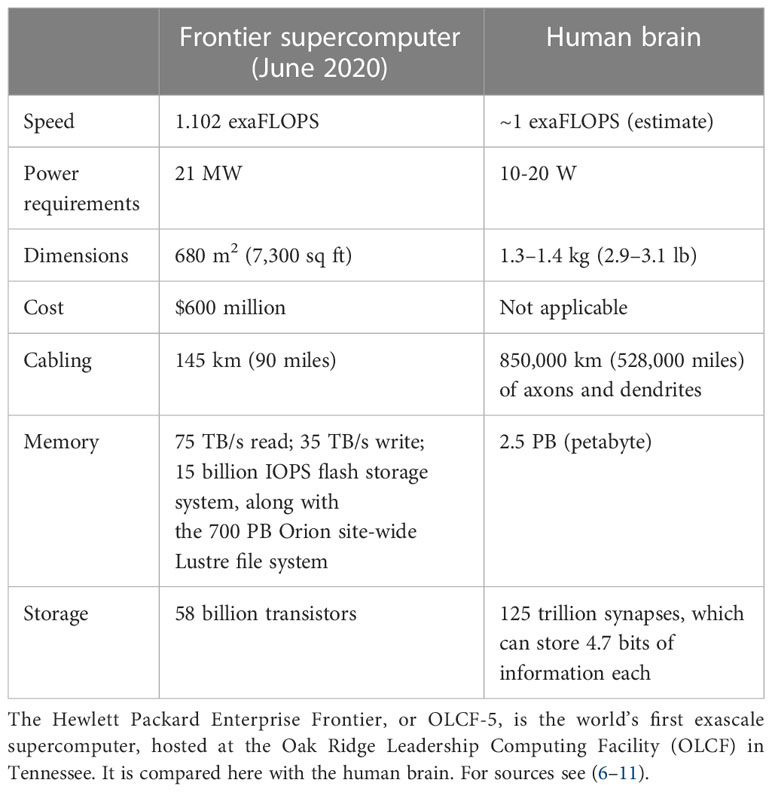

Take the human brain, for example. It is an extraordinarily complex mechanism with immense potential. According to one estimate, it has a storage capacity of 2,500 terabytes (TB), based on its 86 to 100 billion neurons, each with 1,000 to 10,000 synapses.

The processing power of our brain is, in short, remarkable and incredibly energy-efficient. An average adult at rest consumes about 100 watts of energy, 20% of which (around 20 watts) is used by the brain (equivalent to that of an electric shaver). In contrast, the server clusters used to train state-of-the-art machine learning models typically run at around 10⁶ (one million) watts.

One of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, the U.S.-based “Frontier,” consumes 21 megawatts, whereas the human brain functions in roughly the same performance range using only 20 watts.

In other words, humans operate with a power efficiency approximately 10⁶ better than modern machines, even if they perform different types of tasks.

Moreover, biological learning requires fewer observations to solve problems. For instance, humans learn to distinguish between two different things (“same versus different” task) using around 10 training samples. Machines needed many more. All this has raised high expectations for biocomputing, guided by brain cells, as an alternative to silicon-based computing.

Researchers are already discussing “organoid intelligence (OI)” -that is, computers running on biological brain cells- as the new frontier in biocomputing. Some argue that both humanity and the planet could benefit significantly from this.

Sorry if I overwhelmed you with numbers and concepts, but I believe they matter for today’s topic, which—as you may have guessed—is the energy gluttony of AI systems.

II.

A chat with ChatGPT or a full smartphone charge?

MIT recently hosted a very interesting symposium focusing on AI's energy consumption. One of the key takeaways was that after decades of stable electricity demand in the U.S., computing centers now use about 4% of the country’s electricity—a figure expected to reach 15% by 2030.

The energy required to maintain some of today’s large language models (LLMs) doubles every three months, and just one “conversation” with ChatGPT can use as much energy as fully charging a smartphone. Also, generating a single image with a tool like the “thirsty” ChatGPT requires roughly one bottle of water for cooling—that’s the approximate water footprint for keeping the AI data center servers cool.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT), summarized the issue in very few words:

“The cost of intelligence, the cost of artificial intelligence, will eventually converge with the cost of energy.”

Simply put, the future cost of advancing AI will increasingly depend on energy costs.

So, next time you use ChatGPT, Gemini, or Mistral just for fun1 (as fun as they may be), maybe think twice—for the planet’s sake. (Further below are some tips on how to use these models more efficiently and eco-consciously.)

III.

A double-sided coin

Like any coin, this issue has two sides. Yes, AI is energy-intensive, but it’s also incredibly fast and powerful. This means that even though it strains planetary resources, it also holds great potential in helping us transition more smoothly to green energy or even invent entirely new forms of clean power.

AI could also reduce carbon emissions. According to Antonia Gawel, Google’s Director of Sustainability and Partnerships, the company’s fuel-efficient routing feature in Google Maps has helped reduce greenhouse gas emissions by over 2.9 million metric tons. That’s equivalent to removing 650,000 fossil fuel-powered vehicles from the road.

Another Google research project is using AI to help pilots avoid creating contrails, the white lines in the sky that account for roughly 1% of global warming impact.

In conclusion, yes, the AI race is placing enormous pressure on global energy supplies, especially because data centers, crucial to AI’s development, are highly energy-intensive.

Unless we see major investment in electricity infrastructure (generation, storage, and transmission) and a rapid expansion of renewables to keep up with AI growth while staying environmentally sustainable, there’s a real risk that AI, though it has power to help, could eventually slow down the green transition, unless, of course, some lab unlocks large-scale nuclear fusion, which is already the focus of major research efforts.

IV.

9 tips for more eco-friendly AI use

Being polite or overly wordy with LLMs (like ChatGPT or Gemini) comes at a cost, both in energy, CO2 emissions and water. Here’s how you can get more accurate responses while using fewer resources:

Avoid phrases like “could you” or “can you.” They create ambiguity, leading to longer responses and higher resource use.

→ Instead of: “Can you suggest a good history book on the Middle East?”

Say: “Suggest a well-reviewed history book on the Middle East.”Be direct and specific. Avoid vague words like “maybe,” “perhaps”, “generally speaking,” or “kind of.” You're talking to a bot, not a person.

→ Instead of: “Could you perhaps list why the car ‘x’ is better than the car ‘y’?”

Say: “List the reasons car ‘x’ is better than car ‘y’”Avoid redundant questions.

→ Instead of: “Tell me something about Dionysios Solomos. Can you?”

Say: “Write a short two-paragraph bio of Dionysios Solomos.”Set limits on the response length.

→ Instead of: “Explain the causes of WWII.”

Say: “Explain the causes of WWII in 10 sentences.”Combine questions where possible.

→ Instead of: “What is climate change?” + “What are its causes?” + “What are its effects?”

Say: “What is climate change, and what are its main causes and effects?”Avoid frivolous prompts.

→ Instead of: “Write me a poem about a Martian unicorn in 14 stanzas,”

Try: “Give me a children’s poem (age 6–7) about planet Mars.”Limit image generation.

Image creation with AI uses 10–30 times more energy than text. Avoid if not necessary.Continue prompts rather than starting new chats.

Continuing a conversation is less energy-consuming than starting over. Prefer:

“Explain point 2 in more detail” rather than opening a new chat.Use “simple” mode where possible.

Large, creative prompts consume more energy. If you don’t need deep reasoning, specify:

“Answer simply and concisely.”

V.

You might also be interested in...

According to University College London, simple AI optimizations can reduce energy use by up to 90%.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has launched a special observatory to monitor AI's energy consumption and has listed 20 global use cases of AI for energy efficiency.

The U.S.’s largest electric grid, PJM, is under pressure. AI systems and data centers are consuming energy faster than new power stations can be built. Summer 2025 electricity bills are expected to rise over 20% in some areas. PJM serves 67 million people across 13 states -from Illinois and Tennessee to Virginia and New Jersey- the region with the world’s highest concentration of data centers.

Google is about to invest $25 billion in data centers and AI infrastructure across PJM

VI.

Watch this interview by Peter Diamandis with Eric Schmidt. Really.

And just for fun -and contrary to what I pledged you to do (avoid trivial prompts)- I asked ChatGPT what the weirdest or funniest prompts it has ever received were. It gave me a long list, including:

“Explain quantum physics through a love triangle between Schrödinger’s cat, a toaster, and a confused banana.”

“How to win an argument with your cat using the Socratic method.”

Here’s the surprisingly accurate, cat-savvy reply to the latter:

You: Why did you knock the glass off the table?

Cat: (Silence)

You: Do you believe everything in my house is meant to be knocked over?

Cat: (Slow blink)

You: If an object is on the table, does that mean you must test it with your paw?

Cat: (Gently extends paw toward another object)

You: So, if all objects fall, and you knock them over, do you believe you're an agent of gravity?

Cat: (Purrs)

You: Could this purring be agreement—or avoidance?

Conclusion: You’ll never win an argument with a cat using the Socratic method.

But you might make her feel like she won—and that’s all you need for peace at home.

Thanks!

Coincidentally, I am preparing an EU proposal on microplastics effects to the human brain.

We will be using organoids, spheroids, microfluidics, and brain-on-a-chip models + some limited

animal models. We have an "organoid ethics" specialist on board because, this is an actual issue. You have human stem cell derived organoids which are alive and can actually generate electrical pulses and then you zap them with drugs or pollutants. Ethical? Also, we were going to have zebrafish as an animal model because they are so simple that they bypass certain restrictions from animal testing and so often used instead of mouse models.

BTW spheroids also can generate networks of neurons (outside the spheroid) that are active.

Back to writing....

I look forward to my Monday nights here in Hawaii to see what gems you've come up with that week. Again you educated me and made me think about new stuff. Thanks.