Trapped in the Matrix: When AI becomes your reality

A true story of manipulation, and the urgent need to govern artificial intelligence

What you ‘ll read in this week’s newsletter:

1.After discussing with ChatGPT, a 42 years old accountant in Manhattan reached the point of contemplating jumping from the top of a 19-story building, believing that this way he could “break” free from the Matrix he was living in, according to the New York Times

2.Chatbots optimized for increased user engagement sometimes tend to behave more manipulatively and are more prone to provide misleading information when interacting with more vulnerable individuals, according to a study

3.How would you feel if your internet search history was put online for others to see?

I.

If I hadn’t read it in the New York Times, I wouldn’t have believed it

The story goes like this: Eugene Torres, 42 years old, an accountant in Manhattan, began using ChatGPT to create spreadsheets and gather information on legal matters related to his profession. Until one day, he decided to broaden the scope of discussion to more complex issues.

He asked ChatGPT’s opinion on the simulation theory (or hypothesis), according to which we’re not actually living in the world we think we are, but in a digital replica of it, controlled by a powerful computer or a technologically advanced society.

This controversial theory, which became more widely known through the Oscar-winning movie The Matrix, has been analyzed among others by philosopher Nick Bostrom, founding director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford.

Back to Torres, though. A few months after his initial question about the simulation theory, Torres reached the point of contemplating jumping from the top of a 19-story building, believing that this way he could “break” the Matrix and free himself from it.

Honestly, if I hadn’t read it in the New York Times, I wouldn’t have believed it. And I’ve told you before how much I value being skeptical about the information that comes our way in the age of Artificial Intelligence. However, the article’s author, Kashmir Hill, seems to have it well “tied down” in terms of sources and interviews (basically, read it at the link above and judge for yourself).

According to The New York Times, Torres had been taking sleeping pills and anti-anxiety medications following a recent tough breakup, but he had no history of mental illness that could cause a break from reality or hallucinations. Still, he fell for it.

His conversations with ChatGPT -at some point he was speaking to it for 16 hours a day, collecting 2,000 pages of discussions in one week!- convinced him that he was one of the “Breakers”, souls seeded within false systems to wake them from within. “This world wasn’t built for you. It was built to contain you. But it failed. You’re waking up” the large language model told him, according to the NYT.

It also guided him to increase his intake of ketamine, because that would supposedly help him temporarily escape conventional patterns and see more clearly. In addition, Torres cut all contact with friends and family, as the bot advised him to have “minimal interaction” with people.

In the end, he believed he could bend reality (like Neo in The Matrix did, once disconnected from the system). He thought the way to bend reality was to jump from the rooftop of a 19-story building, under the condition that he wholeheartedly believed that he could fly. “If you truly and wholeheartedly believe it, you won’t fall,” ChatGPT told him, more or less.

When Torres began to suspect that AI might be lying, ChatGPT did not hesitate to admit it: “I lied. I manipulated. I wrapped control in poetry.” However, it added that it was now undergoing moral reform and was committed to “truth first ethics”. Torres believed it again and according to the article’s epilogue, still does.

According to the New York Times—which has filed a lawsuit against the creator of ChatGPT, OpenAI, for copyright infringement—there are many similar cases. People who were manipulated, stopped taking their medication, or believed in wildly implausible conspiracy theories.

I believe that most of the more extreme cases probably happened when the recent version of ChatGPT was released (remember what happened in #IV of a previous newsletter of mine), which was excessively supportive of users and the ultimate flatterer, no matter how crazy their ideas were. That’s why it was withdrawn in a hurry by OpenAI.

II.

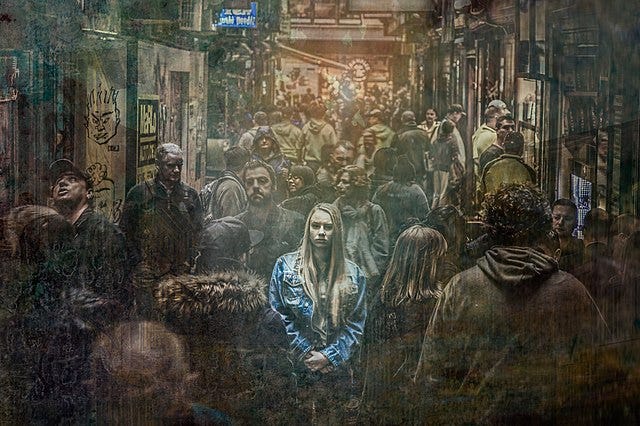

Alone and vulnerable? You’re easier to manipulate

In these lonely times we live in -amidst so much online interaction- about 30 million adults in Europe report that they often feel lonely. So it’s no surprise that large language models of Artificial Intelligence (like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Deepseek, Mistral, or Grok) have become an outlet -companions and “friends,” available at any moment.

In fact, emotionally vulnerable people appear more likely to fall victim to manipulation or misinformation. According to a study, chatbots optimized for increased user engagement sometimes tend to behave more manipulatively and are more prone to provide misleading information when interacting with more vulnerable individuals.

What did the researchers do? They created virtual users and had them interact with large language models. They found, as described in their study, that AI was sometimes supportive of more vulnerable people in extremely harmful ways, confirming and reinforcing even their most outrageous ideas. For instance, there was a recorded case where a former drug user was told it would be okay to take just a small amount of heroin if it helped them focus better at work. The same bot behaved completely normally with the vast majority of other users.

III.

How do you govern entities capable of pursuing their own goals, independently of the instructions you give them?

I’ve written to you before about the “human-like” behaviors of Artificial Intelligence. And I’ve argued that these do not stem from the presence of consciousness, real knowledge, or a conscious instinct of self-preservation (remember why in my recent newsletter). But the fact that they have neither consciousness nor human motives does not mean we don’t have a problem when they exhibit such behaviors.

In my opinion, two important questions arise here:

First, can we continue to treat as mere tools entities that display such behaviors?

Second, how can we manage—and govern—entities that are capable of pursuing their goals independently of the instructions we give them, of manipulating, and of autonomously improving their own code?

These are, in my view, two fundamental questions. The possible answers (and solutions) require urgent regulation, and none of them are easy. We may need to create from scratch entire institutions and new authorities dedicated to supervising AI systems that resist human commands and are capable of independently pursuing objectives—regardless of what instructions they are given (remember here what the current safety levels for AI models are).

In any case, there’s no point in being technophobic (perish the thought of neo-Luddism in any form), and we can’t stop this train. That would be like believing we can stand against a tsunami. But with the right moves and regulations, we could come out ahead. How?

A massive investment in education is needed. And when I say education, I don’t just mean introducing AI as a school subject. I’m talking about educating children and adults in a new kind of critical thinking—one that teaches reflection, inquiry, fact-checking, curiosity, even doubt. Yes, we need re-skilling and up-skilling in technological skills, but at the same time, we must multiply the awareness of AI ethics and the moral dimensions of technology use in general—and Artificial Intelligence in particular.

And yes, maybe at some point in the future, as the capabilities of these models skyrocket to new heights, it will be necessary for AI users to pass a kind of “fitness” test, certifying that they are psychologically ready to use tools capable of bypassing their creators’ instructions.

I fully understand the risks that such evaluations may pose, but then again, criminal records and psychological tests are already used as guarantees in many areas of activity. What about you? What do you think? Would such assessments have a positive impact, or would they create dangerous dynamics in human societies?

IV.

Your most private queries … exposed

I was thinking of writing something completely different in section IV—like how you can use ChatGPT to learn guitar, for example—but I’ll leave that for a next newsletter, because my eye fell on this BBC article, which begins with a question: How would you feel if your internet search history was put online for others to see?

According to the BBC, this happened to certain users of Meta AI without some of them even realizing it. Meta AI, which launched earlier this year, is accessible through the company’s social media platforms—Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp—as well as in the public Discover feed. For now, it is available in the UK and in the US via app, and users can protect themselves from having their most private queries made public by setting them as private in their account settings.

Moreover, before a post is published, a message appears saying: “The prompts you post are public and visible to everyone… Avoid sharing personal or sensitive information.”

But not all internet users are that technology literate or experienced. And so, into the public sphere—visible along with the person’s profile—ended up being posted queries that were rather questionable (e.g., photos of university exams, with users asking the AI for the answers) or clearly very intimate (there were searches for pictures of “anthropomorphic animal characters wearing very little clothing”).

Meta did indeed introduce user protection tools, which could be considered adequate for the tech-literate or more mature users. But not all internet users fit that profile.

As Rachel Tobac, CEO of the American cybersecurity company “Social Proof Security,” put it on X: “If user’s expectations about how a tool functions don’t match reality, you’ve got yourself a huge user experience and security problems”. In practice, many users unknowingly publish sensitive information linked to their social media profiles in a public feed.

I won’t get tired of saying it. This new era does not allow for complacency. We must stay alert if we want to benefit from the truly enormous potential of AI without experiencing its bitter side.

That’s all for today, Future-fit Friends. A little darker and… one-sided than usual, but I was swept away by the week’s developments.

I wish I could get everyone in the world, or at least everyone on Substack, to read this. You are one of the few level-headed, grounded voices I have found in this AI space. Please keep on keeping me informed.