Why algorithms sometimes prefer armed robbers over teenage scooter thieves

From crime prediction to job ads, health care to future intelligence — exploring the urgent need for more diverse, fairer, and transparent AI

What you'll read in this newsletter:

Sometimes, AI gives a better shot at the future to an armed robbery offender than to a teenage girl who stole a scooter. Bias in algorithms isn't just theoretical, it can shape real-life opportunities and justice outcomes.

Right now, cutting-edge AI research is concentrated in just a handful of universities, mostly in the U.S. and China. In the private sector, ten tech giants dominate innovation: Google, OpenAI, Amazon, Apple, IBM, Microsoft, and Meta in the U.S.; Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent in China. How does this closed circle influence AI bias?

Back in 1974, when computers weighed two tons and took up 200 square meters, the legendary Arthur C. Clarke made predictions that now read like prophecy (Video)

If you’re only using ChatGPT as a fancy search engine, it’s time to meet Tutor Me. Let it teach you something, like how to play the guitar or create an AI agent.

I.

Sensitivity and Bias

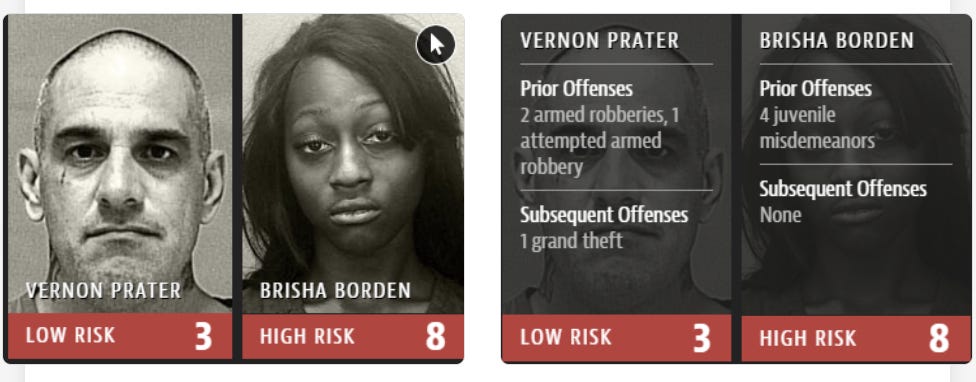

Case One: A few years ago, a young African-American girl named Brisha made a juvenile mistake: along with a friend, she took a child’s bike and scooter from outside a house and rode around the neighborhood. They were eventually caught. Around the same time, a white man named Vernon committed two armed robberies and attempted a third.

When an algorithm was used to assess which of the two individuals was more likely to commit a future crime, it gave Brisha a risk score of 8 out of 10, and Vernon just 3 out of 10 -where 10 indicates high risk and 1 is low.

This algorithmic bias was exposed by a major investigation published by the independent news outlet ProPublica, and I strongly encourage you to read its findings, even though nearly a decade has passed since their publication.

Case Two: Research at Carnegie Mellon University found that Google ads for high-paying jobs (with salaries over $200,000) were significantly more likely to be shown to men than to women.

Case Three: In the U.S., an algorithm was used to assess the healthcare needs of different social groups. It used past healthcare spending as a baseline metric. However, since Black patients in the U.S. often have reduced access to health care (due to economic disparity), their previous spending was lower. The algorithm, therefore, incorrectly assessed them as healthier and assigned them fewer healthcare resources.

These three examples illustrate, with disturbing clarity, how algorithmic evaluation (and bias) can influence justice, healthcare, and labor markets.

II.

Why is AI biased?

As programmer Cathy O’Neil aptly put it, "Algorithms are opinions embedded in math."

Put simply, they reflect the biases of their creators — especially regarding specific human groups (based on race, gender, class, nationality).

AI is like a baby. It may come into the world with genetic traits, but it starts as a tabula rasa. The 'parents' —its programmers— feed it data from which it draws opinions and goals. If the data it receives contains stereotypes, prejudice, or racism, it will likely adopt them. AI learns from the data it’s trained on. And if that data is flawed, its decisions will be, too.

III.

The brilliant Inma Martinez

My first deep dive into the topic of algorithmic bias came through a conversation with Inmaculada (Inma) Martinez, who years ago earned a place on the list of global AI pioneers..

I met her in 2018, in Sharjah, UAE, at the International Government Communication Forum, under the patronage of Sheikh Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi.

She was the first person I heard speak with such passion about the risks of bias in algorithms:

"You don't want a society run by biased algorithms," she told me. "The future lies in building machines that are programmed to have neutral approaches to reality. It’s not easy. We spend days ensuring we’ve coded without any bias, because if you move even a millimeter off-center, the whole system can tilt into prejudice."

Unfortunately, algorithmic bias continues to be omnipresent, even though steps have been taken to improve the situation.

IV.

From Narrow AI to General Intelligence

Now consider that examples like those I described in my introduction relate only to what is called "narrow" or "weak" Artificial Intelligence, algorithms that can perform specific tasks only (for the definitions, you can refer to the footnotes in the previous newsletter).

But exponential advances are being made in the transition toward General Artificial Intelligence (AGI), which could one day (if it ever becomes reality) make important decisions entirely without human input. What happens then? If a biased AI makes a flawed decision, who do humans appeal to? Will there be institutions to hold such systems accountable, systems to which humans can appeal to claim their rights?

V.

The Homogeneity Problem — And the Power of Nine

I described (in many words, to be honest) the problem, so let me move on to the big question. How can we build fairer AI systems? The answer, as Dr. Epaminondas Christofilopoulos (UNESCO Chair in Futures Research) told me, is inclusion.

"Currently," he said, "the leading research in AI is concentrated in a few elite universities -mostly in the U.S. and China. In the private sector, the major players are just ten companies: Google, OpenAI, Amazon, Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Meta in the U.S., and Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent in China”.

The issue? The people building the systems that may soon govern lives come from an incredibly narrow, homogenous group, mainly white and Chinese men, most of whom graduated from a handful of Ivy League universities.

These algorithms reflect the values and assumptions of this small, elite circle.

Unless we involve a far more diverse range of people in designing AI, the consequences for humanity could be stark.

VI.

What Would Arthur say today about AI?

Back in 1974, computers were giants in size and weight, but dwarfs in capability compared to today. Mainframes often weighed over two tons, filled entire rooms of 200–400 square meters, and were used mostly by governments, major universities, and corporate giants. And yet, they were far less powerful than a modern smartwatch.

The reason I’m taking this little journey back in time is because I was once again captivated by the foresight of the great Arthur C. Clarke, whose books I devoured as a child with awe and impatience, and who continues to amaze me as an adult. Let me remind you of one of his most timely reflections:

“Before you become too entranced with gorgeous gadgets and mesmerizing video displays, let me remind you that information is not knowledge, knowledge is not wisdom, and wisdom is not foresight. Each grows out of the other, and we need them all.”

I was reminded of Clarke again recently when I came across a spine-tingling interview he gave decades ago on ABC. It’s absolutely worth watching, a display of startling prescience that flirts openly with prophecy.

In this 1974 interview, Clarke predicted:

"Someday computers will allow us to live wherever we like. Any businessman or executive will be able to live anywhere in the world and do their work through such a device. This means we won't need to stay stuck in cities; we can live in the countryside or wherever else we want and still have full interaction with other human beings."

Remember. It’s 1974 and a computer weighs two tons, takes up 200 square meters, and has less processing power than a smartwatch.

And Clarke didn’t stop there. When the interviewer asked if machines might some day take over from the humans, he answered:

"Computers will surely take over many of our lower-level mental activities, and someday they will be intelligent in every sense of the word. And then there will be two intelligent species on this planet, and that will be a very interesting situation." someday replace us, he answered:

What do you think Clarke would say today about the current state of Artificial Intelligence? Let’s open the conversation: What kind of present would a mind like his have imagined for us — and how close are we to it? Your turn.

VII.

ChatGPT, teach me how to create an AI agent (or play the guitar)

Most of us use ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude like fancy search engines — we swap Google for a question to AI and call it a day. But these models can do so much more than just answer queries. Their true potential lies in how creatively we use them. And the best part? There’s nothing to lose by experimenting.

Take ChatGPT's Tutor Me for example, created in collaboration with the famous Khan Academy. Tutor Me can become your coach in any endeavor (and will do it seriously).

I gave it a few prompts -both in English and Greek- and I encourage you to run your own experiments -the results are genuinely impressive.

Here’s one of the prompts I used:

"I want to learn guitar in 30 days. Please act as an expert guitar teacher. Create a detailed learning plan that will help me build proficiency in this skill.

The plan should include daily tasks, exercises, and goals for each day, with a gradually increasing level of difficulty.

Each day’s session should be no longer than one hour, and by the end of the 30 days, I should have a solid foundational understanding of how to play the guitar.

Present all the information in a table format for easy reference.

Include supporting resources (links, articles, videos, tutorials) for each step."

I used a similar prompt for creating AI agents — and in both cases, the results blew me away.

Whenever a link was broken or didn’t lead where ChatGPT said it would, I simply asked it to replace the link — and of course, it did. You can tailor your goal to whatever you want to learn and how you want to learn it, and let AI guide you.

So, what do you want to learn — and which AI tools are you using as your personal mentors?

Wow--so much useful information in such a short space. Thank you for creating and offering these insights.

Now off to Tutor Me!